Loud Minority

In the aftermath of the Great Earthquake of East Japan on March 11th, 2011, the entire nation was facing the cold and hard reality of vulnerability against massive earthquakes. Seismologists say fault lines entered an active phase, and the magnitude 9.0 earthquake was just a prelude to more to come.

The world was introduced to live images of Fukushima Dai-ichi Nuclear Power Plant, about 300 kilometers north of central Tokyo, being hit by a massive tsunami, which disabled all emergency safety measures and left the hazardous fuel rods open to leak radiation and contaminate vast areas in the days to come.

The nuclear disaster ignited national conversation on the energy policy: how to sustain the lifestyle in one of the most and best industrialized nations and who should carry the burden of this controversial method of creating electricity while no one, including government officials and Tokyo Electronic Power Company, the owner of the facility, knows what to do when accident of this kind happens. The public opinion was awakened by this disaster to study and examine their everyday lives and energy issues. After the quake, all 51 reactors were shut down for the sake of both maintenance and public sentiment. Divided pro and anti-nuclear rhetoric started filling national newspapers, airwaves, and the Internet.

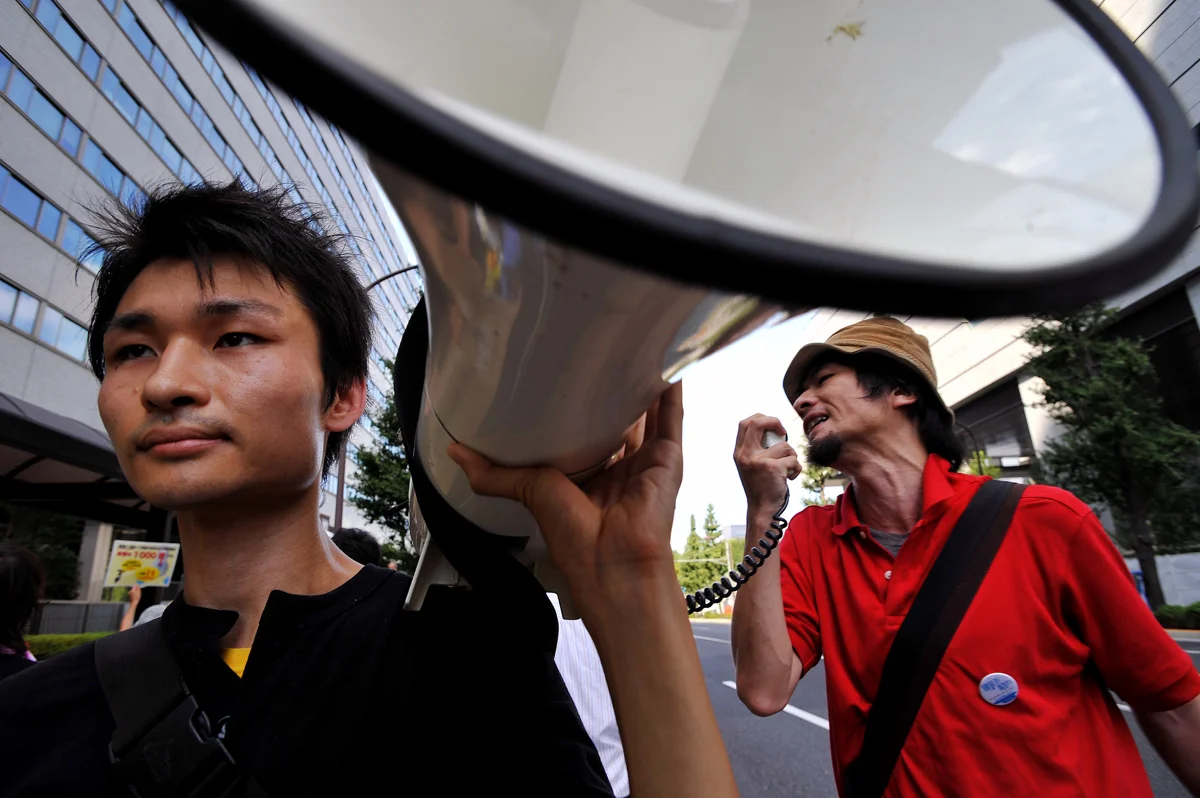

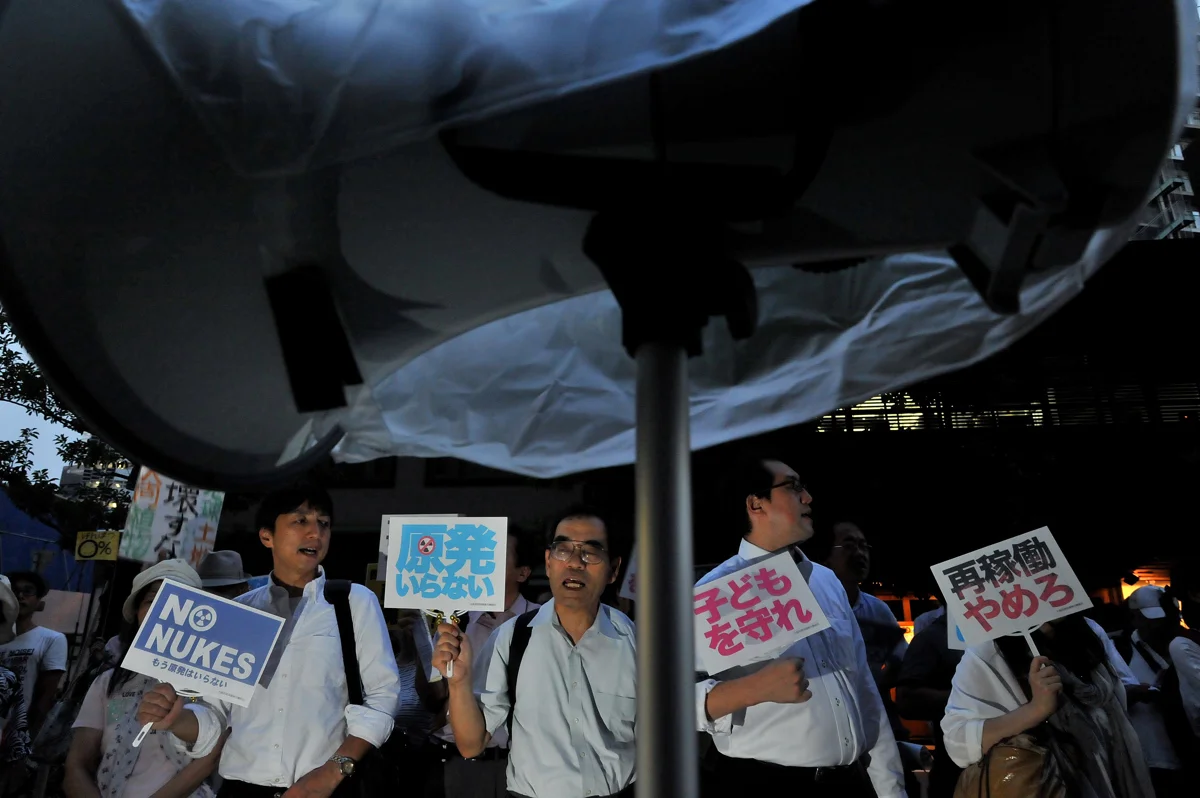

Spending over a year without compensating for the loss of electricity from nuclear generators, then Prime Minister Yoshihiko Noda decided to restart the operation of Oh-i Nuclear Power Plants in Fukui Prefecture on July 5th, 2012. The justification was to meet the high electricity demand during “an expected hot summer”, but it was widely and somehow openly known that the Prime Minister couldn’t resist high pressure from pro-industry and business communities. The reactivation triggered nationwide anti-nuclear uproars. Spontaneous weekly demonstrations were held in locations such as the Prime Minister’s residence in central Tokyo and the headquarters of Kansai Electric Power Company in Osaka, the owner of Oh-i Nuclear Power Plant.

The protest spread all over Japan, but significantly in major metropolitan areas such as Tokyo and Osaka. Words fly through social networking tools and drew tens of thousands of protestors to the streets at its peak. Yet while politicians cannot present alternative energy plans and the majority of anti-nuclear public opinions seem not to be reflected in policy-making processes, it was matter of time before the growing movement would lose its momentum. Hitting a deadlock, it spread a pessimistic mood that the civilian movement may not deliver.

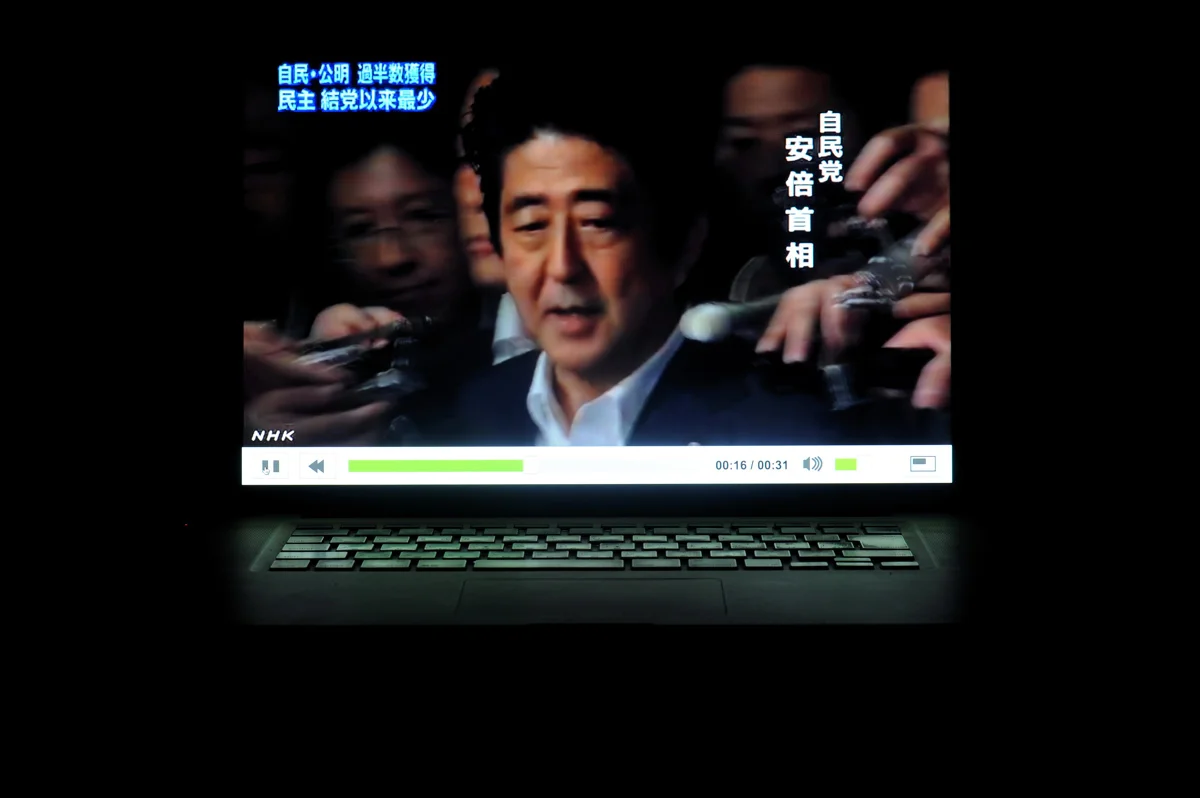

The Lower House election of the Japanese parliament on December 16th, 2012, was critical as the first general election after the quake. It had the lowest voter turnout in the post-World War II record, fewer than 60%. The ruling Democratic Party of Japan lost a majority of seats to the conservative Liberal Democratic Party in a landslide fashion. The next Prime Minister, Shinzo Abe, is pro-business/industry and has already made clear that he will give the go-ahead on both the restart of existing reactors and building new ones.

Then, six months into his administration, on July 21st, 2013, Prime Minister Abe and his ruling party LDP won the Upper House general election and created a majority in both chambers. Ironically, this election was the first case in which an Internet campaign was legalized. Cynics say the anti-nuclear movement had its short momentum because of the power of the Internet, but lost the democratic process to it as well.

When the situation in Fukushima is still deteriorating with no end in sight, it is crucial to document the Japanese public’s will to keep voicing collective concern over pro-nuclear energy policies by current administration. As a comeback party that endorsed the increase of reactors all over Japan so aggressively throughout decades despite the nation’s seismological position, so far new administration offers no viable solutions to the mounting problems after the quake and catastrophic nuclear disaster. This is a work in progress.

2011年3月11日に発生した東日本大震災の後、日本全体が巨大地震に対する脆弱さという冷たく厳しい現実と向き合うこととなった。地震学者たちは、断層帯が活動期に入ったとし、マグニチュード9.0の地震は今後さらに続くであろう地震の前触れにすぎないと警告している。

世界中の人々が目にしたのは、東京から北へ約300キロにある福島第一原子力発電所が巨大津波に襲われ、すべての緊急安全対策が機能を失い、高濃度の放射性燃料棒が露出し、広範囲にわたる放射能汚染が数日間で広がっていくという生々しい映像だった。

この原発事故は、日本のエネルギー政策に対する全国的な議論を呼び起こした。高度に工業化された日本という国の生活をどのように持続させるのか。そして、このような重大事故が起こった際に、政府関係者も東京電力も誰一人として対応策を持ち合わせていない中、誰がこのリスクを伴う発電方法の責任を負うのか。原発事故を機に、人々の間にエネルギー問題と日常生活のあり方についての意識が芽生え始めた。地震発生後、日本国内にある全51基の原子炉は、点検と国民感情への配慮のために停止された。以降、賛否が分かれる原発を巡る論争が新聞、テレビ、インターネット上にあふれ出した。

それから1年以上が経ち、原発の電力を補う明確な代替手段がないまま、当時の野田佳彦首相は2012年7月5日、福井県にある大飯原発の再稼働を決定した。理由は「猛暑が予想される夏の電力需要に応えるため」とされたが、実際には経済界・産業界からの強い圧力に屈したという見方が広く、ある意味では公然と共有されていた。この再稼働決定をきっかけに、全国各地で反原発デモが巻き起こった。首相官邸前や関西電力本社前などで毎週のように自発的な抗議活動が行われ、東京や大阪などの大都市圏を中心に、SNSを通じて情報が広まり、ピーク時には数万人規模の人々が街頭に繰り出した。

しかし、政治家たちが代替エネルギー政策を打ち出せず、反原発の世論が政策に十分に反映されない中で、この市民運動は徐々に勢いを失っていく。行き詰まりを見せ始めると、「この運動では社会を動かせないのではないか」という悲観的な空気が広がり始めた。

そして、震災後初の国政選挙となった2012年12月16日の衆議院総選挙では、戦後最低の投票率(60%未満)を記録。与党・民主党は大敗し、保守系の自由民主党が圧勝した。新たに首相に就任した安倍晋三氏は経済・産業重視の立場から、既存の原発再稼働および新設を進める方針を明確に打ち出した。

さらに就任から半年後の2013年7月21日、参議院選挙でも安倍首相と自民党は勝利を収め、衆参両院で多数派を形成。皮肉なことに、この選挙はインターネットを使った選挙運動が初めて合法化された選挙でもあった。反原発運動はインターネットの力によって一時的に盛り上がったが、最終的にはそのインターネットによって民主主義のプロセスに敗れたという皮肉な見方もある。

福島の状況が未だ収束の見通しを立てられないなかで、現在の政権による原発推進政策に対して、日本の市民が引き続き声を上げていく姿を記録することは重要である。かつて日本中に原発建設を推し進めてきた与党が政権に返り咲いた今、震災と原発事故後の深刻な問題に対し、いまだ実効性のある対策を提示できていない。本作は、そのような状況のなかで現在進行形の取り組みである。